I want to start this post by noting things that I took from my engagement with the recommended resources on disability, before outlining how I might respond to these reflections.

Disability and dispossession

In the short film including a performance and interview with Christine Sun Kim, the passage which most affected my approach to developing inclusive pedagogic practice was when Sun Kim describes that ‘while growing up’, she ‘saw sound as [hearing people’s] possession’. This sentence completely reframed how I understood the barriers that society places on D/deaf and hearing impaired individuals. Captionless or non-signed onsite lectures inaccessible, for example, but they perform a kind of epistemic violence that not only impacts D/deaf and hearing impaired students but all, as it emphasises that the learning is an activity that exists within a sonic space, something which cannot be produced through different kinds of non-sound-based communication.

In my context as a Writing Tutor for Y3 students, I will endeavour to map out the different aspects of this engagement and to identify the assumptions that might be engineering discriminatory epistemic demarcations. [More to come on this going forward!]

Intersectional approaches

Both the interview with Villissa Thompson and essay by Khairani Barokka emphasised the ways that both campaigns and art pieces can fail to see intersectional forms of marginalisation – Thompson noting the under-representation of disabled people of colour within the disability movement, and Barokka not recognising the way that her own show was detrimentally impacting her health.

These both speak to a principle that Davies (2019) has written about regarding inclusive curriculum design for students with dyslexia: if disabling mechanisms are removed for all students, then courses don’t have to rely on diagnoses or disclosure to ensure that students are supported [also referred to as ‘critical universal design’]. This notion of embedding or ‘centrally’ locating strategies for inclusivity can begin to facilitate intersectional approaches to curriculum design (Davies, 2019, p. 92), which is particularly pertinent in a UAL contexts where, as Carys Kennedy noted in our session on 10/05/23, there is a significant disparity between the disclosure of disability between International students and Home students.

Working with SpLDs in role as Writing Tutor

With a particular focus on specific learning difficulties (SpLDs), and in light of the above reflections, there are aspects of my role as Writing Tutor that I can shift towards an embedded, intersectional approach. When I begin to work with students, I’m aware if they have an ISA and I ask them informally in our first 1:1 if there are any approaches to research which feel suited to them, and anything I can do in the short or long term to support them with the unit. I make it known that I’m always available via email if they want to reach out. As we meet every three or four weeks between September and late January / early February, I will ensure that all references/comments that I have made are recorded in an email which I will send to them in the days after each 1:1. I try to ensure that accompanying each reference is a brief and clear explanation as to why I have included it. I’m aware that different students prefer different kinds of resources to engage with and I try to cater to this.

The development of my approach unfolds below in three sections, each broadening my practice.

- Embedding direct strategies

The above approach to my role as Writing Tutor feels somewhat removed from specific strategies that I can place across all my engagement with students. It fails to recognise the possibility that some students will not feel comfortable disclosing certain SpLDs to me, or that some will be unaware of their SpLDs (Davies, 2019). Thus various ideas spring to mind. When I first meet the Y3 students I’ll be working with, which is in a group context, I will dedicate some time to taking all students through text-to-speech software and tools for reducing visual stress signposted by UAL, and get the students to try out some of this software on their own devices during the session. Additionally, as well as highlighting why I’m encouraging students to read certain texts, I will also highlight the passages that are the most important.

- Weighing up nuances

My role as Writing Tutor, however, does differ from what Davies (2019) might refer to as curricula design, and as such my approach may also have to be individualised. While some strategies for inclusivity can cut across all my engagement with all students, it is also true that I will have to adapt my teaching to different students. For example, some students will want to receive comments before a tutorial, others would prefer to have comments from a tutorial recorded and sent to them afterwards. Some students will feel less comfortable disclosing any needs in informal in-person conversation, preferring to do it in an online/written platform as they may need time to reflect on how they describe their needs.

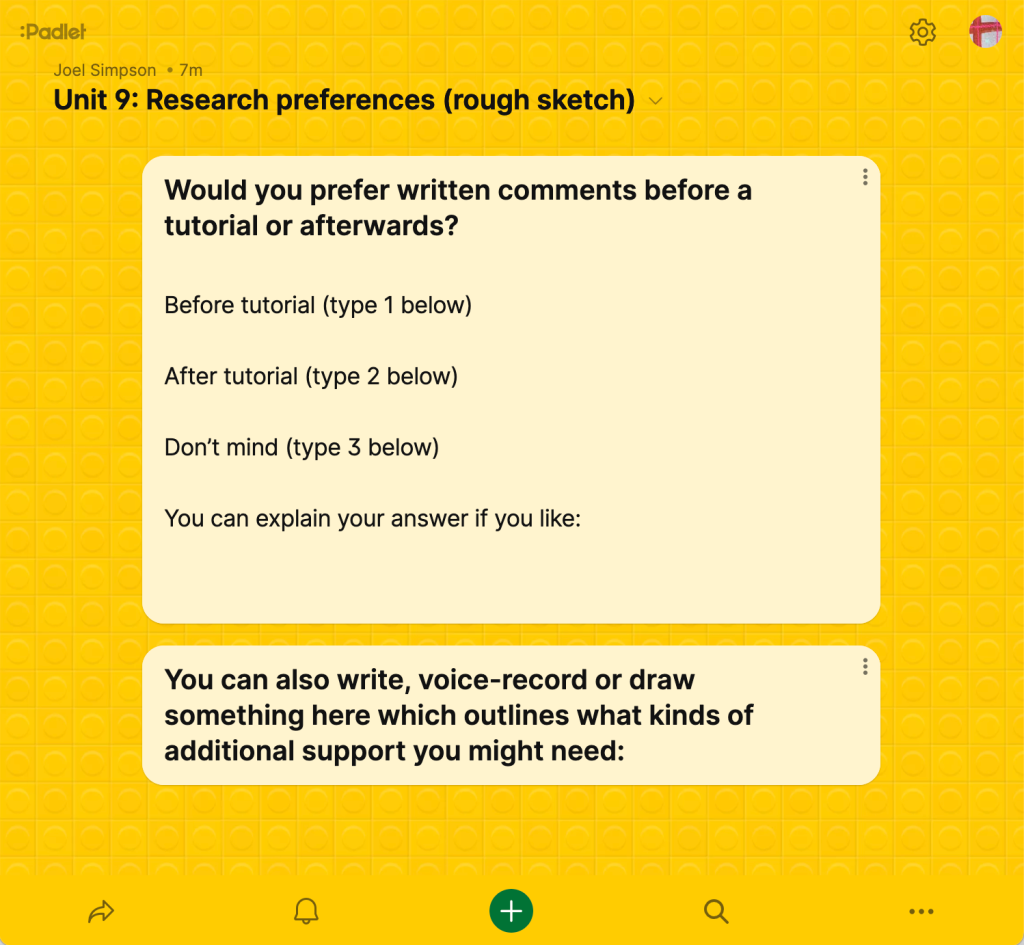

I’m envisaging here a platform, such as a Padlet page, that students can use to refer to any needs they may have (this will be only accessible to me). They could have the option of changing their answers in this platform throughout the term. They can choose to follow specific questions that I’ve set for them to answer (see below), but they can also construct their own responses, through audio-record or drawing.

Below is a quick rough sketch of what the platform could look like. Unfortunately Padlet does not allow for different font sizes or text spacing from what I can see, which are things that the British Dyslexia Association’s Dyslexia Style Guide notes are important considerations.

- Epistemic transgression

Outside of strategies both embedded and individualised, there are also wider epistemological questions. As I noted with regards to the interview with Christine Sun Kim, problematic epistemological framings emerge in a context where disabling mechanisms are reproduced (eg. learning is sound-based). While I will inevitably have blind spots and assumptions that may only be revealed through de-biasing strategies as outlined by Patricia Devine (2012, p. 8) – particularly through ‘increased opportunities for contact’ – there are other key ways that I can address the more complex notion of epistemological violence that I may have enacted in my pedagogy.

One important method for resisting inaccessible conceptualisations of research and learning is to address these conceptualisations head on: What is research for? What are the different ways we can research and what might they lend to our project? What interactions can I have in my research? When do I most enjoy learning? When do I learn the most?

As Jain (2022, p. 33) notes of the many possible contributions of ‘crip time’ to assessment practices, inclusivity is not only a material or infrastructural project, but one that concerns reimagining temporalities and systems. I hope that by exploring the above questions in different contexts with students can open up possibilities of an epistemic transgression or subversion where new ways of re-imagining our teaching and learning can emerge in order for disabling mechanisms to be dismantled.

3 responses to “Post 5: Disability: Developing a pedagogic practice for the removal of disabling barriers”

Hi Joel,

I really enjoyed your thoughtful reflection on the short film featuring Christine Sun Kim and learning about the impact it had on your approach to developing inclusive pedagogic practices. It was inspiring to see how Sun Kim’s statement about sound as a possession completely reframed your understanding of the barriers faced by D/deaf and hearing impaired individuals. Your recognition of the epistemic violence perpetuated by captionless or non-signed onsite lectures and its broader implications for all learners was particularly insightful.

I am impressed by your commitment to mapping out the different aspects of engagement and identifying the assumptions that may contribute to discriminatory epistemic demarcations. Your proposed intersectional approach to curriculum design, drawing from the concept of critical universal design, is both necessary and commendable. By focusing on removing disabling mechanisms for all students, you aim to create an inclusive environment that doesn’t rely on diagnoses or disclosure for support.

I appreciate your dedication to your role as a Writing Tutor and your intention to shift towards an embedded, intersectional approach. Your consideration of specific learning difficulties (SpLDs) and your efforts to cater to individual student needs are truly commendable. The strategies you mentioned, such as introducing text-to-speech software and tools for reducing visual stress, as well as providing clear explanations of important passages, demonstrate your commitment to accommodating diverse learning preferences. Using a platform, like a Padlet page, to allow students to express their needs and preferences throughout the term not only provides flexibility but also empowers students to construct their responses in ways that suit them best. It’s clear that you value individualisation and are willing to adapt your teaching methods to create an inclusive learning environment.

I found your exploration of epistemological questions and your desire to challenge traditional conceptualisations of research and learning to be really thought-provoking. Your emphasis on reimagining temporalities and systems, as well as your intent to foster epistemic transgression and subversion, demonstrates your dedication to dismantling disabling mechanisms within pedagogy.

You clearly have a deep understanding of the issues surrounding inclusivity, intersectionality, and epistemology in education.

I am inspired by your commitment to developing an embedded, individualised, and transformative approach to your role as a Writing Tutor.

It was great to see your perspective on inclusive teaching and some of the strategies you intend to use with your students. Our teaching environments and contact are different in many ways (frequency of contact, one-to-one versus whole class), but there are many approaches here that I could adopt.

I can introduce the whole class to reading aids such as text-to-speech software and screen rulers/tints. In one-to-one tutorials, students often ask to record our conversation, and this is something I encourage – transcription tools like Otter.ai are incredibly helpful for remembering the main points discussed, and some students find it challenging to listen, reflect, respond, and take notes simultaneously (it helps my own AuDHD when I have my own tutorials on PgCert).

These don’t just have benefits for students with SpLDs but also for students whose first language isn’t English. And, as you point out, not every student with a learning difference is aware that they have it.

The Padlet idea is something I’ll trial next term. I’ll admit I hadn’t considered its accessibility aspect (font size and spacing), so thanks for bringing that to my attention.

Lastly, Crip Time is something I’m becoming very interested in, as well as reconsidering the different forms that research can take in a creative field.

Incidentally, what is the reference by Davis (2019)? I tried to find it in the resources folder and would love to read it.

Hi Joel,

I’m impressed by how thoughtfully you are considering how to embed these ideas into your role. The idea of creating a padlet for students to complete ahead of tutorials is a good idea- in my experience, it is a battle getting students to complete any paper work ahead of a tutorial (specifically tutorial forms), but I wonder if its a more informal format, students might feel more disposed to do it.